If the NT wants to silence coroners from exposing systemic racism, then the Federal Government must step in.

Author: George Newhouse, CEO, National Justice Project

The Northern Territory Government is preparing a response to Coroner Elisabeth Armitage’s detailed inquest findings into the 2019 police shooting of Kumanjayi Walker.

The coroner made more than 30 recommendations regarding police culture, training, accountability, and community engagement, but instead of focusing on the conduct of the NT police the government has publicly flagged a major review and potential overhaul

of the Coroners Act 1993 (NT).

Any plan to undermine the coroner is not just dangerous, it is legally regressive, morally indefensible, and in direct conflict with the lessons Australia promised to learn from the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody nearly 35 years ago.

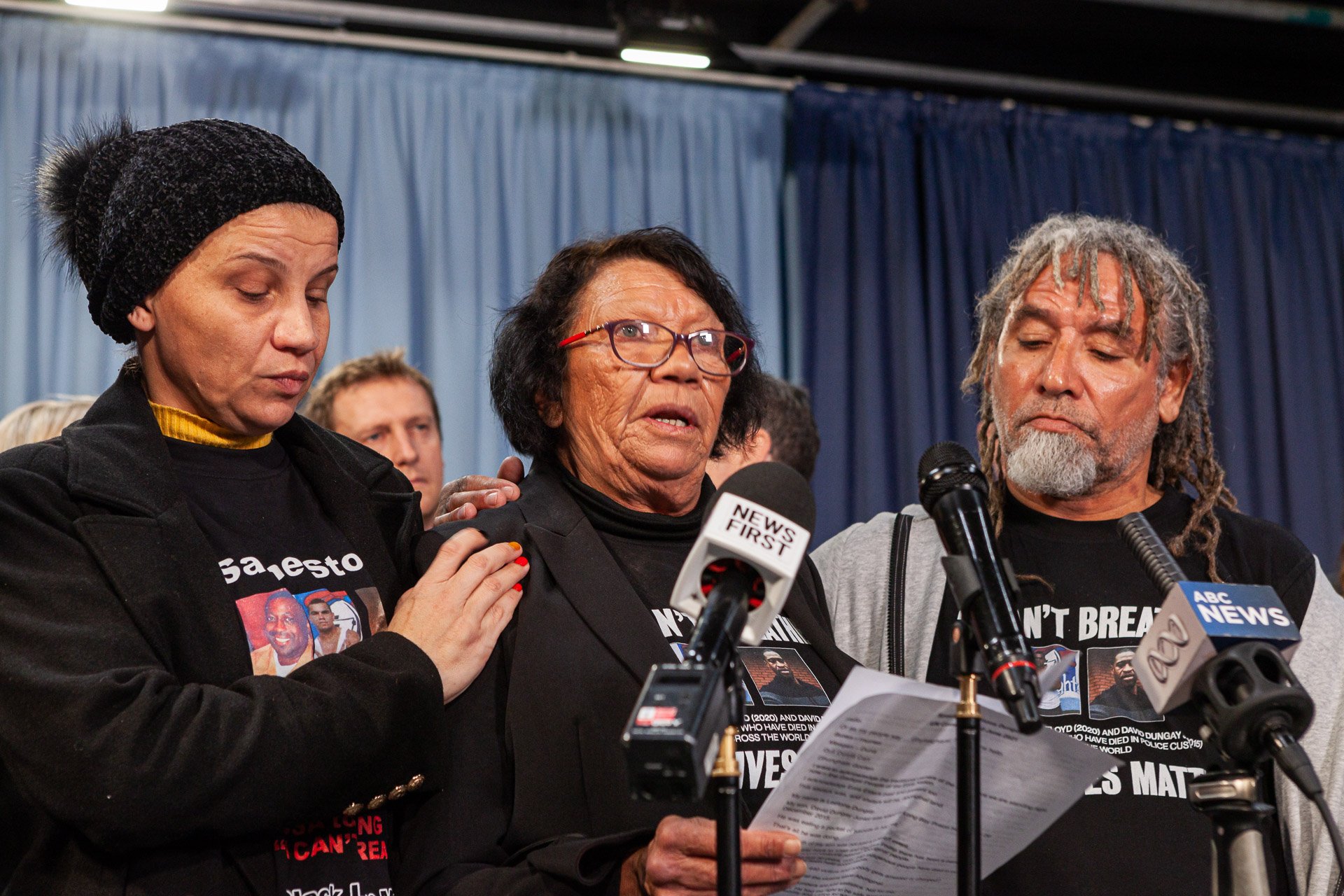

As the lawyer representing the grieving family of Kumanjayi White (another recent death in custody), the government’s approach risks undermining the outcome of that inquest before it has even begun.

Initial responses to the Kumanjayi Walker findings and recommendations suggest that the NT government wants to turn away from the uncomfortable truths about how First Nations people are treated by institutions, like the police, that should be free from discrimination.

We must be on guard to ensure that decades of life-saving reforms are not undone by the proposed amendments, putting lives at risk.

The Kumanjayi Walker inquest, conducted with care and thoroughness by Coroner Elisabeth Armitage, exposed deep cultural failings, operational misconduct, and embedded racism within the NT Police. It has already led to a commitment from the NT Police to implement an Anti-Racism policy but instead of committing to reform, the NT Chief Minister has responded with deflection and distraction and now suggests there is a need to review the Coroners Act.

To understand the history of the expansion of coroners’ powers in the 1990s, and why any attempt to curtail them is so dangerous, we must return to the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody which explicitly called for post-death investigations into the circumstances surrounding a death and for comment on the quality of care, treatment, and supervision of people who died in custody.

These reforms were not symbolic … they were essential. They ensured that coroners could act as a voice for justice, particularly for families and communities who rarely see accountability from child protection, police, health, or carceral systems.

Across the country, there are powerful examples of how coroners have used their powers responsibly to expose systemic failures and make recommendations to try to make change.

The deaths of XY (a First Nations Child in State Care), Naomi Williams, Dougie Hampson, Veronica Nelson, Mona Lisa and Cindy Smith, and Kumanjayi Walker have illuminated patterns that would otherwise remain hidden, honoured the lives lost, and driven critical reforms in child protection, health, justice, and policing.

The process isn’t perfect, but it is improving in many jurisdictions.

What the NT Government is proposing must not roll back three decades of institutional change – born out of the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

That Royal Commission made it clear: coroners should do more than identify the cause of death. They should examine the broader context of deaths in custody—failures of care, racism, medical neglect, inadequate supervision and then recommend systemic change where appropriate.

If the Northern Territory Government refuses to uphold the principles set out by the Royal Commission, then responsibility must shift.

Fortunately, our Constitution provides a way to intervene: Section 122 gives the Federal Parliament full authority over territories. The Commonwealth can override NT laws whenever it chooses. It has done so before, such as in 1997 when it struck down the NT’s Rights of the Terminally Ill Act and when the Howard Government called the Intervention.

The Federal Government has the legal power and the duty to act if the NT seeks to silence the coroner. It should step in immediately and guarantee that coroners retain the right to investigate systemic contributors to death, including racial discrimination, health neglect, and police misconduct.

In fact, it should go further and establish an independent First Nations led investigative body to examine and have oversight of all deaths in custody to rebuild trust with First Nations communities.

The need to intervene is particularly pertinent in response to a broader pattern of regressive and punitive legislative interventions in the Northern Territory. A suite of laws, many of which undermine human rights, including the rights of children and First Nations peoples, have already been pushed through the NT Parliament despite significant community and expert opposition.

These include laws that disproportionately affect Aboriginal communities, raising serious concerns under both community expectations and international human rights frameworks.

It has been 33 years since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. More than 550 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have died in custody since then.

The NT Government’s plan could limit the examination of future deaths so that systemic issues go unchallenged. That’s a betrayal of every person lost – and every family still waiting for justice.

Australia cannot allow that to happen.