The climate crisis is not just an environmental issue, it’s one of the greatest human rights challenges of our time.

Australia has already warmed by 1.5°C since national records began in 1910. According to the Australian Climate Service, even small levels of global heating can drive more extreme heat, storms, droughts and flooding.

These impacts are not something to dismiss as a future fear. Right now, communities’ homes, livelihoods, health and connection to Country are being impacted.

As meaningful government action and accountability continue to fall short, urgent change is needed to prevent the climate crisis from continuing to devastate the people least responsible for causing it.

Why the climate crises is a human rights issue

The climate crisis is impacting human rights right now by undermining people’s ability to live with safety and dignity.

Beyond the immediate danger of heatwaves, floods and bushfires, the long-term negative impacts on health, and food and water security, can put people’s lives at risk.

As the climate changes, food is becoming harder for communities to grow and access, with droughts, floods and rising sea levels damaging farms and local food supplies.

Hotter temperatures and water shortages are also making it harder for people to access clean drinking water and sanitation.

For First Nations peoples, the climate crisis not only threatens the environment, it endangers Country and destroys ways of life that have existed for generations.

How the climate crisis deepens inequality

The climate crisis is amplifying existing injustice, with people who have contributed the least to global heating often being impacted the most. These effects are already being felt across communities:

- First Nations communities are facing some of the most severe impacts. Research shows that land, water and food systems have already been damaged or destroyed, alongside the cultural impacts of the loss of Country.

- People with disability face higher risks during climate-related disasters. United Nations human rights analysis shows that barriers to emergency support make access to safe housing, healthcare, food, clean water, sanitation and essential medicines more difficult.

- Children and young people are also especially vulnerable. Human rights analysis highlights that extreme weather events can increase health risks, disrupt education and reduce access to basic needs such as food and safety.

Decision-making without including affected voices risks causing further harm. When climate responses are developed without centring the leadership and lived experience of Indigenous peoples and other impacted communities, they can deepen inequality rather than address it.

Australian climate justice cases

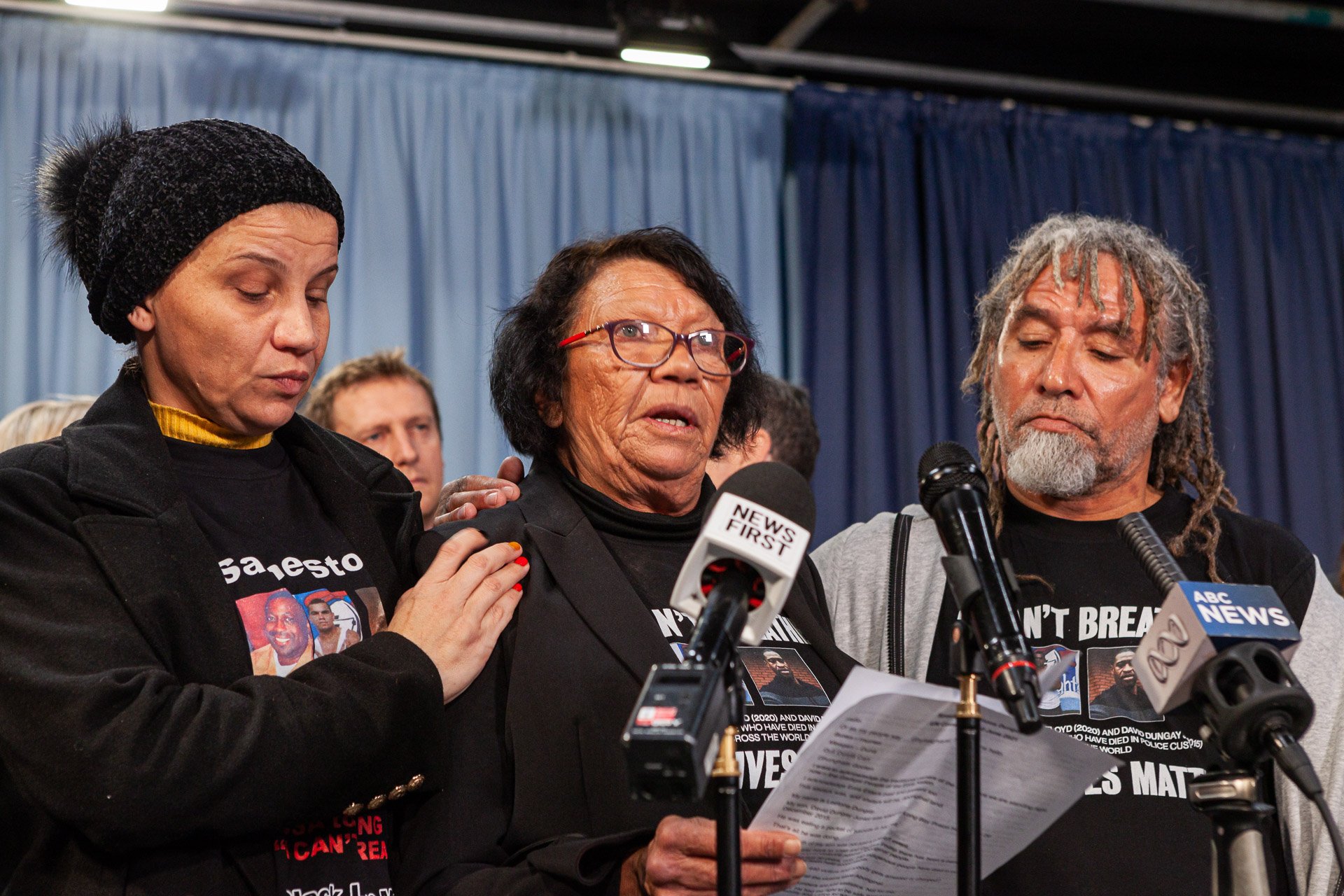

Over the past few years, communities in Australia are increasingly turning to the courts to expose truths and force accountability.

In the Pabai Pabai case (2021), Uncles Pabai Pabai and Guy Paul Kabai, both from the Guda Maluyligal Nation, gave evidence that rising seas are threatening their homes, culture, identity and future on Country. While the Court ultimately declined to recognise a duty of care, the case marked a turning point in how climate harm is understood within Australian law.

While litigation isn’t always easy or guaranteed to succeed, climate justice cases can shift legal and public narratives and build the foundations for future accountability.

Another example of climate justice activism in Australia is Seed mob, a movement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people addressing social, economic, and environmental injustices to ensure fair and just climate solutions for all communities. SchoolStrike4Climate and the Australian Youth Climate Coalition are also urging the Australian governments to address the urgency of the climate crisis.

Why the National Justice Project is stepping into climate justice work

The impacts of the climate crisis are not shared equally, and the communities we serve are among those most affected. As these impacts worsen, so does our responsibility to act. Acting on climate justice is not just essential, it’s urgent in our mission to fight systemic injustice.

LawHack 2026 is our first step into this space, with legal professionals from across Australia working together to address real-world climate harms. Through LawHack, we are laying the groundwork for climate justice work that holds governments and corporations to account and centres the leadership and lived experience of affected communities.

Looking ahead, we will work alongside the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research to consider climate justice in our UTS strategic litigation university clinic.

This clinic will equip future lawyers with the strategic skillset needed to contribute meaningfully to climate justice work and support communities whose human rights are being impacted by the climate crisis.

The climate crisis is accelerating, so must justice.