What is the National Justice Project’s position on the Voice to Parliament?

We support the ‘yes’ campaign on constitutional recognition and a Voice to Parliament. The members of our First Nations Advisory Committee argue that the Voice to Parliament is not the only or final step that is needed to secure First Nations justice, but it will be a major advance in the generational struggle for rights and equality.

Despite legitimate concerns held by some First Nations activists and colleagues, we believe that the Voice to Parliament represents a real opportunity to create systemic change.

We believe that it will be a powerful tool for advocacy that can work alongside and strengthen grass-roots campaigning. Many of our clients have been campaigning for years on issues like First Nations deaths in custody, discrimination in healthcare, and discriminatory policing; if the Voice to Parliament can channel the experiences of our clients into Federal Parliament, then we will be in a stronger position to achieve progress.

What change will constitutional recognition and a Voice to Parliament deliver to First Nations peoples?

We believe that a First Nations Voice to Parliament will help deliver the systemic policy changes that are needed to achieve social justice for First Nations people. Here’s how:

- Power: constitutional recognition will increase the political power of First Nations people, allowing them to work with governments to develop the policies needed to secure First Nations justice.

- Agency: First Nations people will have a real say over the issues that affect them.

- Advice: First Nations people will give practical advice to the Parliament about laws and policies, so decisions that will impact First Nations peoples are made with them, not for them.

- Inclusion: Rather than having bureaucrats and politicians decide what is best for Indigenous people, First Nations people will be included in the policy-making process through consultation.

- Security: The Voice is protected from political interference by being enshrined in the constitution.

- Better outcomes: When First Nations people who know and understand the issues and solutions are consulted, we will be better able to close the gap that still exists between First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians.

What campaigns and actions led to the referendum?

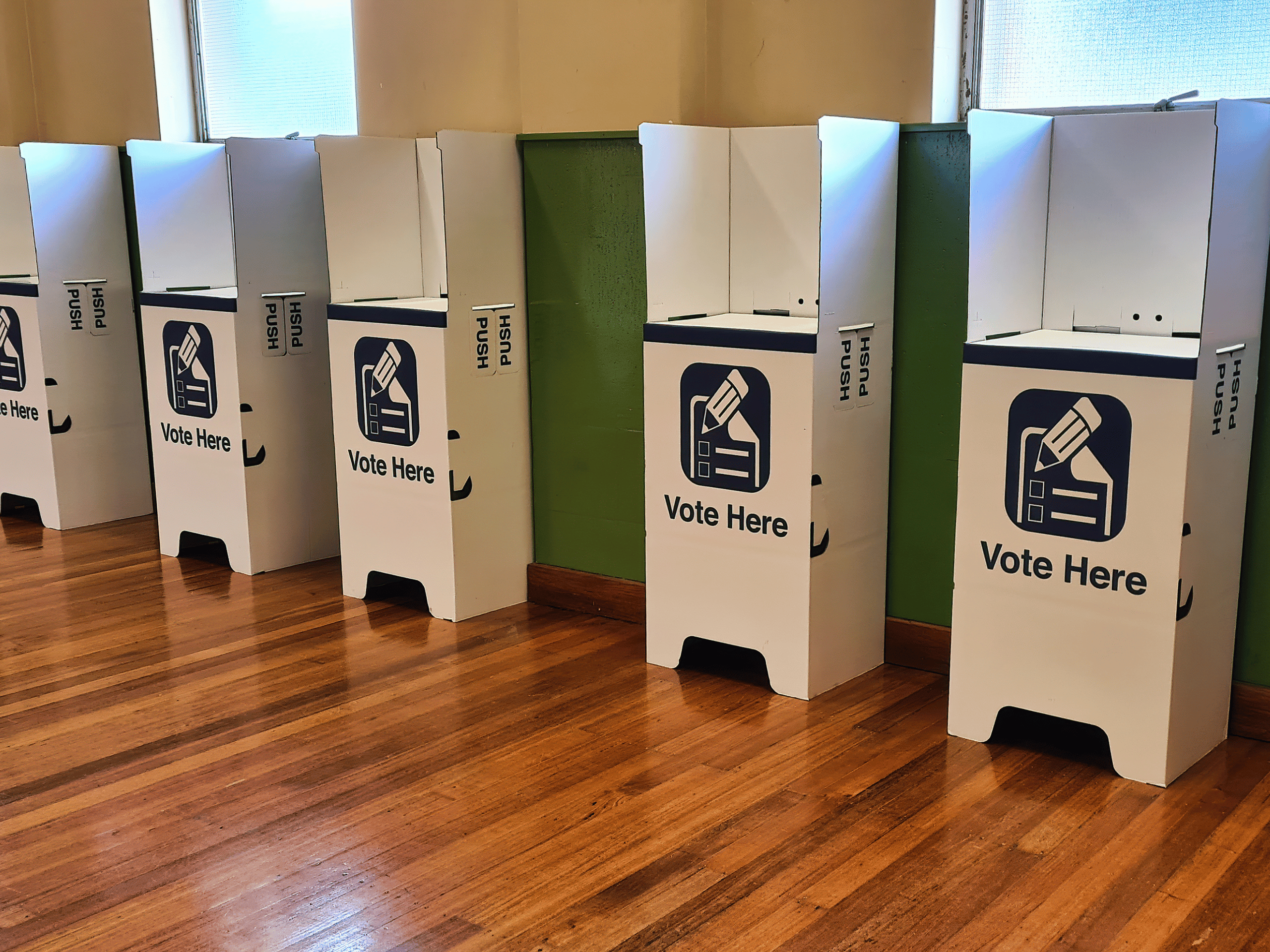

Since Federation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have advocated for constitutional reform to recognise their status as First People of our nation. Now, Australians will be asked to vote on a constitutional amendment to recognise First Nations Peoples through a Voice to Parliament.

In 2017, a First Nations Constitutional Convention brought together over 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders to meet at the foot of Uluru, on the lands of the Anangu people. The majority resolved, in the ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’, to call for the establishment of a ‘First Nations Voice’ in the Australian Constitution and a ‘Makarrata Commission’ to supervise a process of ‘agreement-making’ and ‘truth-telling’ between governments and First Nations peoples.

Following the Statement from the Heart, the Indigenous Voice Co-design Report was produced by Professor Marcia Langton and Professor Tom Calma. Their report was the result of 18 months of consultation with 9,478 people and organisations, including 115 community consultations in 67 locations, 2,978 submissions, 1,127 surveys, 124 stakeholder meetings and 13 webinars.

In May 2022, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese made a commitment to establish an Indigenous Voice to Parliament that is guaranteed by the Australian Constitution. This commitment represents the recognition sought in the Uluru Statement from the Heart and will involve every Australian voter in a referendum to change the constitution.

What is the Voice to Parliament?

The Voice is about two things: recognition and consultation. The Voice aims to provide the foundation for better outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The Voice will be a representative body made up of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from across the country. It will provide advice to the government and parliament about matters relating to the social, economic and cultural wellbeing of First Nations people.

The many issues facing First Nations people are complex, but the people themselves understand the issues that affect their families and communities and are best placed to contribute to the solutions of the issues that they face.

The Voice would be able to table formal advice in parliament, and a parliamentary committee would consider that advice. This advice would not be binding, meaning that there could not be a court challenge, and no law could be invalidated based on this consultation. The Voice would not have a decision-making role, nor the power to veto legislation or government decisions.

An important feature of the Voice is that it is written into the Constitution. This would recognise the special place of First Nations people in Australia’s history, but it would also mean that it could not be shut down by a future government.

The Voice would not deliver services, manage government funding, or mediate between First Nations organisations.

What are the limitations of the proposal?

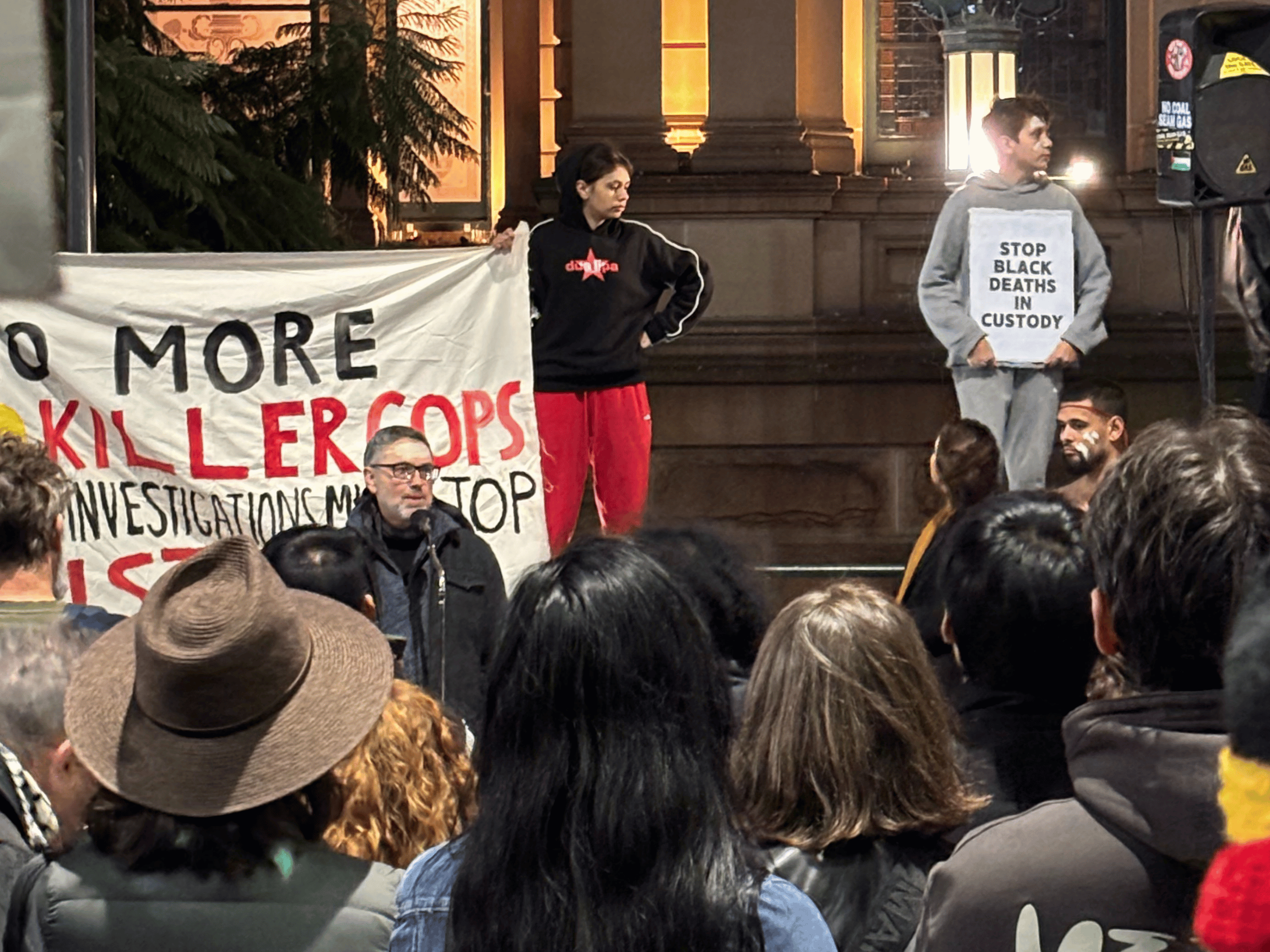

We acknowledge that for many First Nations campaigners, the Voice to Parliament is not a sufficient response to the multiple levels of racism in Australia. Senator Lidia Thorpe has said “we deserve better than a powerless voice; we need a treaty, we want real power, we want real justice in this country.”

Senator Thorpe’s views are echoed by many First Nations activists who wish to see urgent change to address issues like over-incarceration, land rights, housing, child protection, education, cultural heritage and economic participation. Criticisms of the Voice to Parliament include:

- A consultative status is not enough

- Parliament decides on how the Voice is structured

- Concern that sovereignty of First Nations people could be affected by the Voice

- The Voice to Parliament does not prevent governments from discriminating on the grounds of race

- The power of the Voice has been diluted through political compromise over more than a decade

We acknowledge that these concerns are legitimate, and we share the desire to go further than a Voice to Parliament. The injustices that our clients face are deeply rooted in the legacy of colonialism and ongoing systemic racism, so it is unlikely that a Voice to Parliament would resolve these urgent issues in the short-term. However, we believe that the Voice to Parliament represents a significant step forward towards securing justice on some of the most urgent issues facing First Nations people. Therefore, we support the ‘yes’ campaign on constitutional recognition and a Voice to Parliament.