Gamilaroi woman and solicitor at the National Justice Project, Karina Hawtrey, writes for Indigenous X.

It sometimes feels that for every small step forward we take with policy and law reform in this country it’s two steps back.

When just last August, the Northern Territory became the first Australian jurisdiction to legally raise the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 12 it was applauded as a positive step forward. A small step, mind you, when the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and the national Raise the Age Campaign call for a minimum age of 14, and against the backdrop of our country’s appalling youth detention record.

With the landslide election of the Country Liberals in the NT on the weekend off the back of low First Nations voter turn-out, one of the first items on the agenda of the incoming Chief Minister Lia Finocchiaro was to announce that her government would lower the age of criminal responsibility back to 10.

Amongst the suite of law-and-order reforms proposed are new bail laws and “boot camps” for young offenders. Previously, the new Chief Minister had indicated that if elected she would reverse the ban on the use of spit hoods on children in youth detention.

It is a truly horrifying prospect that the NT and we, as a country, cannot seem to learn from our previous mistakes and that we continue to put the lives of children at risk.

Kids as young as 10.

Kids who should be in primary school classrooms not cells.

Clearly nothing has been learned from the shocking images of Dylan Voller sitting spit hooded and strapped to a chair in Don Dale Youth Detention Centres. The findings of the 2017 report of the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory ring out as a haunting warning:

“Children and young people like [Dylan] were incarcerated, ignored and deprived of their basic needs. They were held in conditions some of which were unspeakably bad and treated in a way that meant rehabilitation was impossible. Unsurprisingly, their mistreatment bred more wrongdoing and more significant behavioural issues.”

And it’s not just Don Dale. The record of our nation’s youth detention centres – a nice way of saying prisons for kids – speaks for itself.

In Western Australia, Yamitji 16-year-old Cleveland Dodd became the first young person to die in prison in the State after taking his own life in the notorious Unit 18 wing of the state’s maximum-security prison. A coronial inquest into his death heard from a nurse that her job at the Unit was like working in a “war zone” with some detainees being held in the same cells without running water for 22 hours a day, the UN definition of solitary confinement. Just today, we have heard the traumatic news of another death at Banksia Hill Youth Detention Centre in WA and it’s only a matter of time before it will happen in other institutions, including the NT.

Although only about 5.7% of people aged 10–17 in Australia are First Nations, 63% of the children in detention on an average day in 2023 were First Nations. This means they are 29 times as likely as a non-Indigenous child to be in detention. For children aged 10-13, this figure rises to 46 times. Most of them (81%) are awaiting sentencing.

In the Northern Territory, 97% of the children in youth detention were First Nations and the Chief Minister wants to send 10-year-olds into that mix.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports that First Nations children consistently experience detention at a younger age than non-Indigenous children and at a higher number and rate. Evidence shows that the current approach is only resulting in an increase of recidivism and trauma.

As a human rights lawyer, I have seen the lifelong impact of incarceration on First Nations kids as young as 11, who have been in and out of youth detention and now adult prison. They have been kept in cells for up to 23 hours a day, denied access to schooling, time outside, interaction with other young people, psychologists and First Nations support workers, and they have been diagnosed with serious mental health conditions including PTSD.

These kids come out of prison more harmed than when they went in.

Country Liberal Party Leader Lia Finnocchiaro says that “community safety is by far the greatest issue facing the Territory” but what is being done to protect and care for the kids who are supposedly holding the Territory hostage?

The kids that are engaging in these behaviours and being criminalised are kids who from the outset are vulnerable, kids who don’t have a safe place to hang out or sleep at night. A report released just last week from the National Children’s Commissioner looked at how we can transform child justice to improve safety and wellbeing and found that many of the First Nations children interviewed were dealing with “intergenerational trauma and disadvantage, and children with disabilities, mental health issues, and learning problems.”

The tough reality is that many First Nations kids today face the serious consequences of the intergenerational trauma and poverty that has been caused by the practices of colonisation, from the ongoing removal of children to the disconnection from Country.

If we are asking these 10-year-olds to be held accountable for their actions, we need to consider are we, as a nation, being held accountable for ours?

We need to be listening to the communities themselves to hear what they need to help these kids. We need to be learning from our prior experiences about what works and what doesn’t. We need to be engaging with community-led creative solutions rather than resorting to the lazy and ineffective law-and-order approach of chucking them in prison.

For the taxpayer, it costs $2827.47 per day to incarcerate a young person, a staggering cost of $1.03 million per year. Imagine what could be done if we invested that money into youth workers, support services, education, social housing?

As Yamitji-Noongar woman and Federal Greens Senator Dorinda Cox points out: “The way forward is through evidence-based solutions that address root causes and result in long term change. We know that children need to be with caregivers, connected to Country not sent to boot camps or jails.’

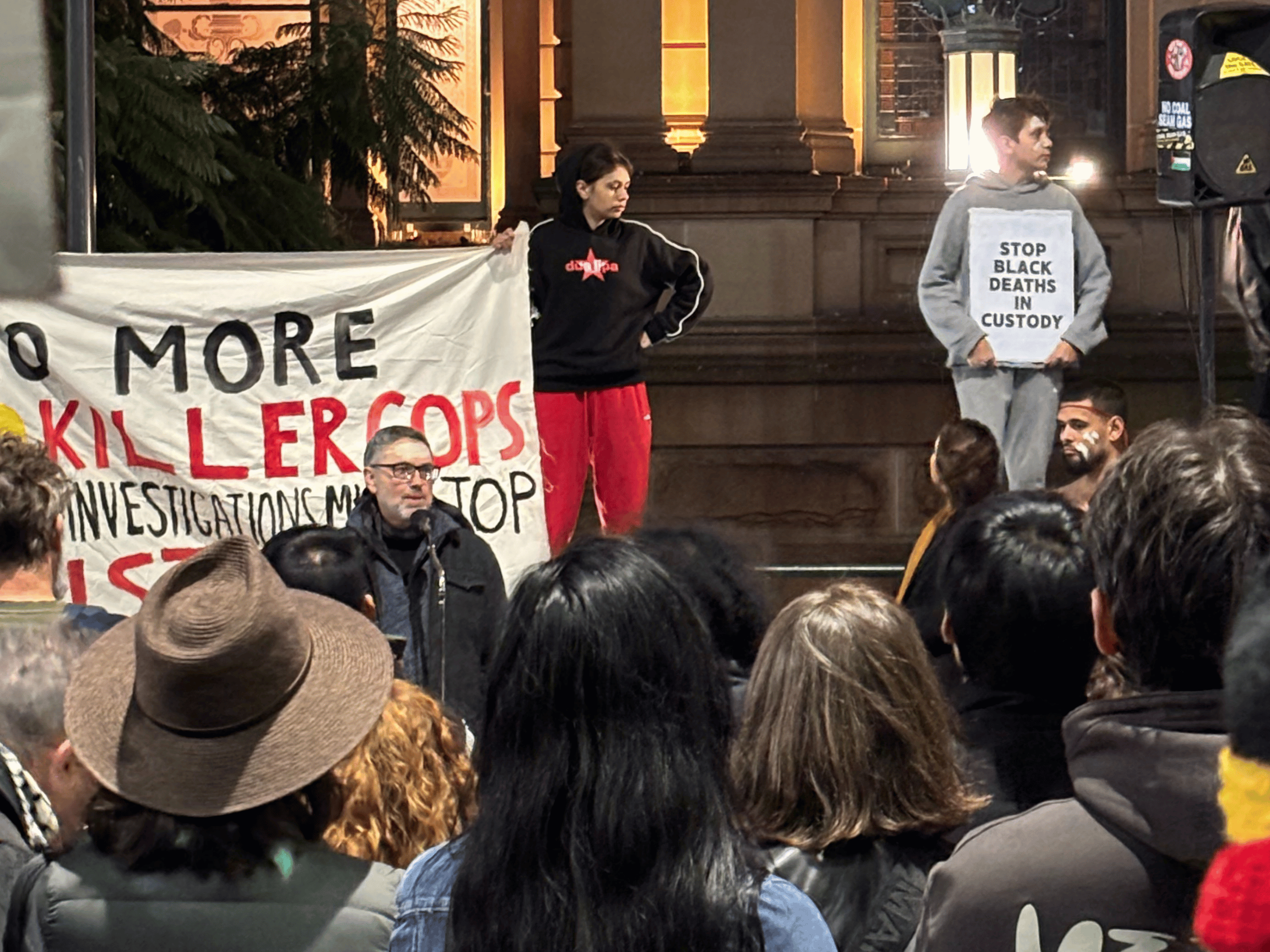

This week we have seen a collective response condemning the NT’s proposed approach from First Nations Peak bodies to the Australian Medical Association and the National Children’s Commissioner.

But the situation in the NT shows us the danger of when locking up 10-year-olds becomes a political football and the real risk that any steps we take forward can be back-tracked just as quickly. Only this month, the Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan reversed Labor’s previous commitment to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 14 by 2027 and lowered it to 12.

Only Tasmania and the ACT have raised the age of criminal responsibility to 14 so far and the challenge is out there for the other State Premiers to act on this issue to prevent further trauma being disproportionately enacted on First Nations kids.