This article by National Justice Project co-founders George Newhouse and Duncan Fine first appeared in the Guardian Australia on 5 December 2023.

It’s depressing but totally predictable that the only time you ever hear about the workings of the criminal justice system is when conservative politicians and their boosters in the media complain about the need to lock people up and throw away the key.

Difficult questions about the balance between the fundamental right to individual liberty and how that interplays with government power over our lives and the right for us to live in a safe and non-violent society can be tossed aside as merely academic.

But these questions actually are profoundly important and go to the heart of what sort of country we want Australia to be.

These issues have been brought into laser sharp focus by last month’s high court decision (NZYQ) that overturned the 2004 Al-Kateb case and that decided that Australia’s government does not have the right to indefinitely detain individuals where there is no meaningful purpose other than punishment and that our government must release those immigration detainees that it has been detaining arbitrarily, in some cases for a decade or more.

No one should be surprised about the way that high court decision has been politicised by Peter Dutton, who seems to want to bring as much heat and as little light as possible to a debate that requires calmness and nuance.

The high court’s ruling that the government could not indefinitely detain a non-citizen if there was no real prospect of their removal from Australia becoming practicable in the reasonably foreseeable future should be uncontroversial.

It simply brings Australia into line with other democracies around the world, where the power to incarcerate and limit our liberty is vested in the courts and not in the hands of politicians.

The high court even mapped out a way forward for the government in its NZYQ decision. The court made it clear that the constitution would not prevent detention of the plaintiff on a proper statutory basis, such as under a law providing for preventive detention of a child sex offender who presents an unacceptable risk of reoffending if released from custody. In other words, when you block out all the red-faced bluster from bombastic politicians, the court has provided a mechanism to keep society safe from the worst offenders.

The response from the government to the high court’s decision is yet another depressing example of leadership with an eye to the next opinion poll and headline, rather than to the rule of law. It has initiated a two-pronged approach: to impose restrictions on liberty through new bridging visa conditions and to draft new “preventative detention” laws that will allow a court to impose detention or other restrictions on liberty along the lines of state high-risk offender laws.

Those new bridging visa conditions are already being challenged in the high court on the basis that they are unconstitutional because they may amount to an ongoing punishment. The proposed “preventative detention” regime for immigration detainees that is being barrelled through parliament as we write follows more closely to the high court’s roadmap by formulating laws that will allow a court to order the preventative detention of only those immigration detainees that pose a risk of harm to the community.

It’s understandable that there is significant concern about the release of violent sexual offenders into the community, and there must be a system for monitoring and tracking people to mitigate the risk of harm to the community. But the sweeping nature of the new preventative detention regime could have unintended consequences.

The political script for these regressive laws is simple. A government starts with sexual offenders, paedophiles and terrorists, the most reviled people in society. They become pawns in a game to garner support for laws that vastly increase the ability of the political and legal system to limit freedoms.

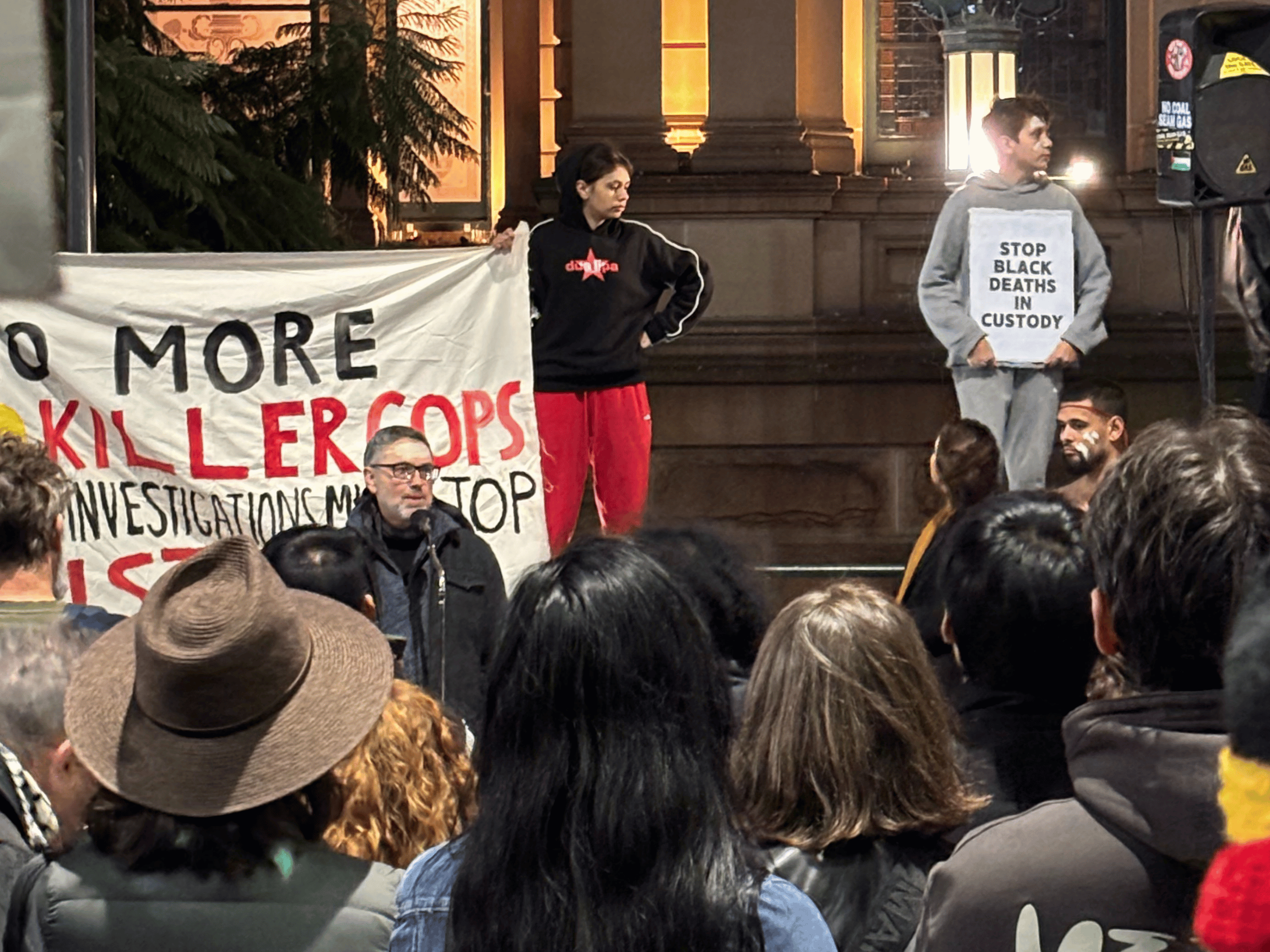

But who will be next to be locked up arbitrarily? Our experience suggests that it will be the poor, the marginalised and First Nations people.

The new federal preventative detention regime will require the government to bring a case against the individual and provide evidence to a court when seeking orders restricting the liberty of immigration detainees. The court will need to balance the rights of the individual against the safety of society and we can only hope that they get it right.

Both major political parties are always quick to commit to the basic human right to individual liberty. But when a tough case comes along – like a stateless person accused of a crime, or an Aboriginal person who has served his time in prison – that commitment disappears.

We are calling for serious scrutiny of these new federal laws, to ward off the dangers of unfettered government overreach. We believe in a fair and just Australia that follows the law and not the whims of politicians.